A couple of weeks ago I submitted a pull request to the main CKAN repo, which was promptly reviewed and merged by my tech team colleague Sergey. On the surface it looks fairly unremarkable, just cleaning up some old code and some tests no longer used. But this code has played a critical role in making possible one of the most important milestones in CKAN’s history, its migration to Flask and support for Python 3.

I’ve been working on CKAN long enough to be allowed telling some old man stories, so gather round I guess…

The setting

Support for Python 3 had been discussed among CKAN maintainers for a long time, several years before the actual end of support for Python 2. At that time though, CKAN was already a large web application built on top of Pylons, a web framework which was state-of-the-art when it was initially adopted by CKAN but that it had stopped being developed. CKAN was stuck in an inactive, Python 2 only framework, and the technical debt was piling up.

Although there was (and still is) a natural successor of Pylons (the Pyramid framework), the decision was made at the time to use Flask which had a much larger community and ecosystem behind it. Once that was decided, there remained the tricky question of how to actually pull it off…

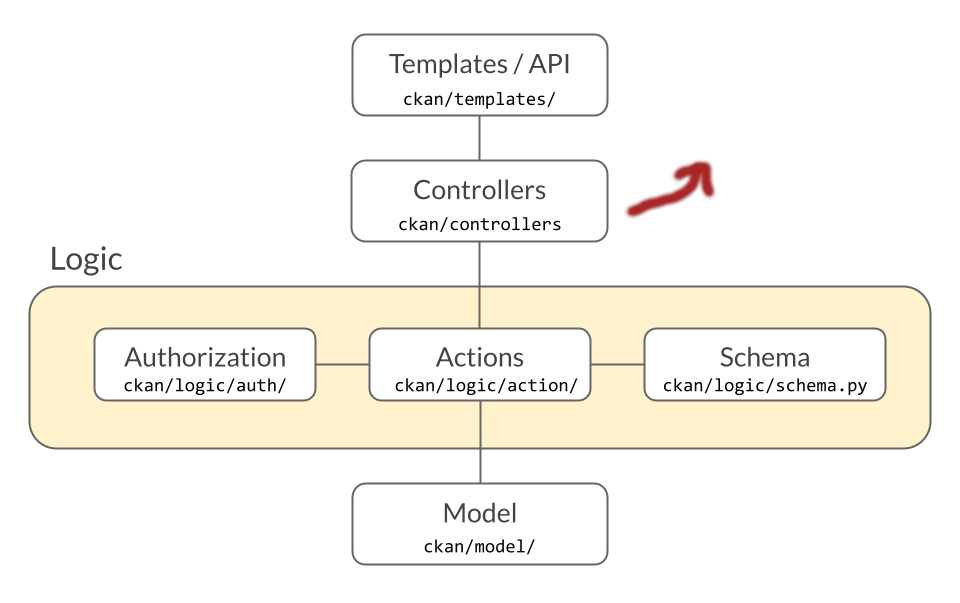

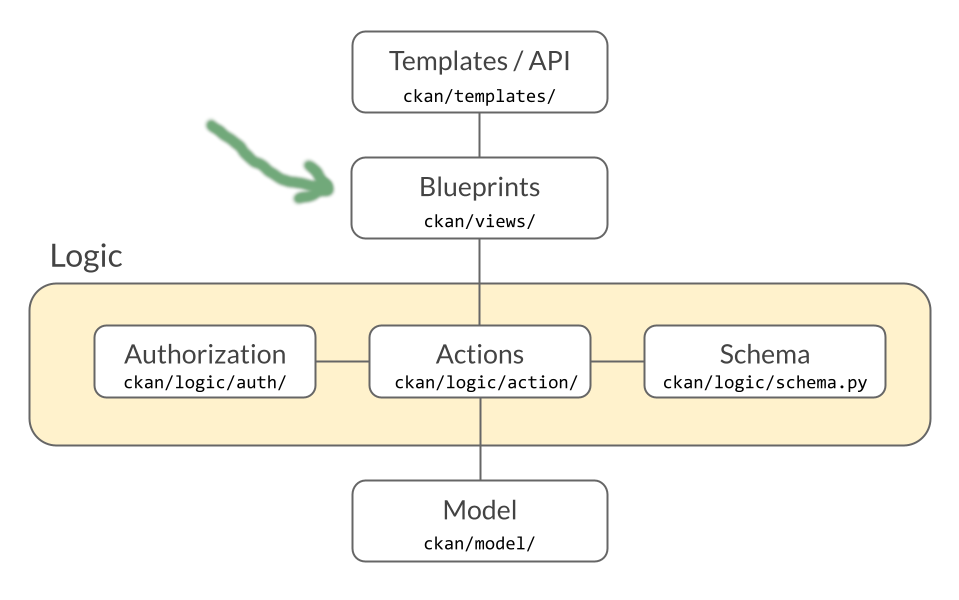

Luckily CKAN had been architectured in a mostly sensible way and had most of the business logic and database models clearly separated from the request handlers (the C in MVC). In theory then, replacing the web framework would just mean replacing what Pylons called controllers:

… with Flask blueprints:

Well, on paper maybe but there were a number of factors that made this work difficult:

- There were about a dozen controllers, some of them huge like the ones handling dataset related requests.

- It was not as clear cut as the diagrams showed (it never is). There were framework-provided objects and variables used in different modules across the codebase (things like

configorsession). - CKAN Extensions are able to implement their own routes and controllers, and backwards compatible support needed to be provided for them during a reasonable period

- We were not a rich project. The different maintainers and the organizations they worked for could not invest a big chunk of resources in a short period of time to work on a clean, full rewrite.

So every time the issue was brought up the sheer size of the changes meant that no action was taken and the can was kicked further down the road.

The idea

Towards the end 2015 and beginning of 2016 the Open Knowledge Foundation was able to secure some funding for work on CKAN. It was not enough to do a full migration but big enough to at least do some preliminary foundation work to kickstart the process.

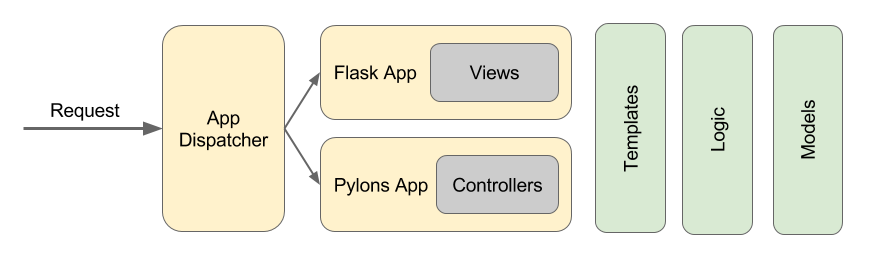

My colleague at the time Brook Elgie and I started thinking of ways to approach this. It soon became apparent that going full Flask was not feasible, for the reasons outlined before. So then I started thinking, if we can’t rewrite everything to use Flask in one go, why don’t we keep both Pylons and Flask running side by side for a while? Each would have their own middleware stack and their own controllers / views and any code at a lower level (actions, authorization, models, etc) would be shared among both applications.

But how would we decide which app would handle each request? Well, we would just ask each application if they understood that request! A small middleware (AskAppDispatcher) at the top of the stack would get the response and show it to the apps, get their responses and decide what to do. Here’s a really technical run down of how a request not yet migrated to Flask would look:

AskAppDispatcher: Hey folks, I just received a GET request for/dataset/timber-exports-2018, what can you do for me?- Flask app: Sorry, no idea what this is

- Pylons app: Yup, that's a dataset page, I can take care of it

AskAppDispatcher: Ok, you take it Pylons app, I'll forward you the WSGI environ

Another more complex situation, involving extensions:

AskAppDispatcher: Hi again, we have a POST request to/user/edit/amercader, does that ring a bell?- Pylons app: Sure, it's the user edit form

- Flask app: Hold on! A loaded extension implements a Flask blueprint that overrides this same endpoint

AskAppDispatcher: Aha, sorry Pylons, Flask takes precedence here. Here's your WSGI environ

The code

Here is a really simplified version of how the AskAppDispatcher middleware worked (you can see the real thing here):

def make_app(conf):

'''

This is the main WSGI app factory

Initialise both the pylons and flask apps, and wrap them in dispatcher

middleware.

'''

load_environment(conf)

app = AskAppDispatcherMiddleware(

{

"pylons_app": make_pylons_stack(conf),

"flask_app": make_flask_stack(conf)

}

)

return app

class AskAppDispatcherMiddleware(object):

'''

Dispatches incoming requests to either the Flask or Pylons apps depending

on the WSGI environ.

Each app should handle a call to 'can_handle_request(environ)', responding

with a tuple:

(<bool>, <app>, [<origin>])

where:

`bool` is True if the app can handle the payload url,

`app` is the wsgi app returning the answer

`origin` is an optional string to determine where in the app the url

will be handled, e.g. 'core' or 'extension'.

Order of precedence if more than one app can handle a url:

Flask Extension > Pylons Extension > Flask Core > Pylons Core

'''

def __init__(self, apps=None):

self.apps = apps or {}

def ask_around(self, environ):

'''Checks with all apps whether they can handle the incoming request

'''

answers = [

app.can_handle_request(environ) for name, app in self.apps.iteritems()

]

# Sort answers by app name

answers = sorted(answers, key=lambda x: x[1])

return answers

def __call__(self, environ, start_response):

'''Determine which app to call by asking each app if it can handle the

url and method defined on the eviron'''

app_name = 'pylons_app' # currently defaulting to pylons app

answers = self.ask_around(environ)

# Enforce order of precedence based on the answers

# Flask Extension > Pylons Extension > Flask Core > Pylons Core

app_name = 'flask_app' # or 'pylons_app' (logic not shown)

return self.apps[app_name](environ, start_response)

We wrapped both the Flask and Pylons applications to implement the can_handle_request() method, which essentially passed the WSGI environ to their internal router modules. Routers translate a request like GET /dataset/timber-exports-2018 to an actual Python function that can handle it and return a response. If the routers found a match for that particular request, it meant that the application could handle it. Here’s how the Flask application did it (again heavily simplified, the real deal is here):

class CKANFlask(Flask):

'''Extend the Flask class with a special method called on incoming

requests by AskAppDispatcherMiddleware.

'''

app_name = 'flask_app'

def can_handle_request(self, environ):

'''

Decides whether it can handle a request with the Flask app by

matching the request environ against the route mapper

Returns (True, 'flask_app', origin) if this is the case.

`origin` can be either 'core' or 'extension' depending on where

the route was defined.

'''

urls = self.url_map.bind_to_environ(environ)

try:

rule, args = urls.match(return_rule=True)

origin = 'core' # or 'extension' (logic not shown)

return (True, self.app_name, origin)

except HTTPException:

return (False, self.app_name)

The Pylons app had a similar method using its own router.

Accompanying this dispatcher were a number of wrappers around common objects from both frameworks that were used to provide a single interface so users wouldn’t have to worry about loading the correct one. They all used a is_flask_request() function that via some heuristics and a tiny bit of magic determined if the current request was served by Flask or Pylons and returned the relevant object. We used Werkzeug’s LocalProxy to make the wrapper thread-safe.

Here is the wrapper for the request object as an example (the rest can be found in the common.py module):

def _get_request():

if is_flask_request():

return flask.request

else:

return pylons.request

class CKANRequest(LocalProxy):

u'''Common request object

This is just a wrapper around LocalProxy so we can handle some special

cases for backwards compatibility.

LocalProxy will forward to Flask or Pylons own request objects depending

on the output of `_get_request` (which essentially calls

`is_flask_request`) and at the same time provide all objects methods to be

able to interact with them transparently.

'''

@property

def params(self):

u''' Special case as Pylons' request.params is used all over the place.

All new code meant to be run just in Flask (eg views) should always

use request.args

'''

try:

return super(CKANRequest, self).params

except AttributeError:

return self.args

request = CKANRequest(_get_request)

The results

This initial version of the middleware plus companion code took several iterations to get right and we had to iron out lots of different issues. For instance, even if a request was served by Flask or Pylons you still needed the router from the other application to be able to work to generate URLs for routes served by the other application. Tests needed to be adapted, more wrappers were required, etc but eventually we ended up with a pretty solid setup to run both applications side by side.

This allowed us not only to migrate individual controllers one at a time but also to tackle specific issues as they came up. The first controller that we migrated was the API one, because it didn’t require any template rendering. CKAN 2.7 included the app dispatcher middleware and the newly migrated API blueprint, and the next version 2.8 already included some more blueprints migrated. In the meantime, extensions could start creating their custom routes via Flask blueprints in order to be future ready.

Finally, CKAN 2.9 was the version that included all controllers migrated to Flask blueprints, and with them full Python 3 support. CKAN 2.9 still supports Python 2 to help sites to transition, but the next CKAN version will be Python 3 only.

And now that it served its purpose and CKAN’s main branch is Pylons-free, it was time to say goodbye to AskAppDispatcher,

the little middleware that could.

In my opinion, the approach we took with this middleware was a great success. It allowed the project to evolve gradually from a very risky situation where the technical debt was a big liability to a one where it is back in sync with modern Python standards and practices. It was a bit crazy, but given our resource constraints we had to think outside the box in order to make the task manageable and maintain compatibility for existing sites.

Rare footage of the CKAN Tech Team working on the Flask migration

(Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B_1bAnLqlMo)